project summary

This website provides scientific argument assessments and corresponding resources across reading, writing, and talking that can be used by teachers, curriculum developers, and educational researchers.

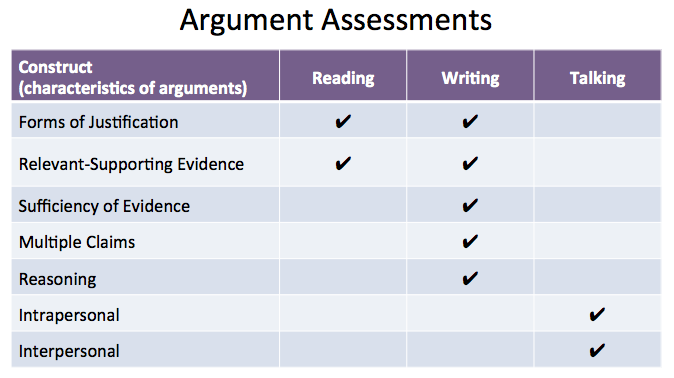

Assessing the quality of arguments is a difficult task. There are often numerous aspects of students’ writing that could be addressed, but it is difficult to know which are the most important. We help with this challenge by looking at specific characteristics (or constructs) of the structure of an argument (e.g. forms of justification, relevant-supporting evidence, sufficiency of evidence, multiple views, and reasoning) and process of constructing arguments (e.g. process, product). By argument, we mean a justified claim. Whereas a claim is a statement that answers a question, justifications are used to support the claim. The table below summarizes the ten assessments we have developed to date.

Assessing the quality of arguments is a difficult task. There are often numerous aspects of students’ writing that could be addressed, but it is difficult to know which are the most important. We help with this challenge by looking at specific characteristics (or constructs) of the structure of an argument (e.g. forms of justification, relevant-supporting evidence, sufficiency of evidence, multiple views, and reasoning) and process of constructing arguments (e.g. process, product). By argument, we mean a justified claim. Whereas a claim is a statement that answers a question, justifications are used to support the claim. The table below summarizes the ten assessments we have developed to date.

assessment design

The BEAR Assessment System (BAS) informed our design of the argumentation assessments (Wilson, 2005). We began the development process by identifying individual (unidimensional) constructs, which are the unobservable (latent) characteristics being measured (unidimensionally) (Wilson, 2005). The second stage of development focused on expanding, or mapping, the construct into qualitatively distinct levels along a continuum from high to low (Wilson, 2005). These theoretical models of cognition known as construct maps are based on an understanding of expert disciplinary knowledge as well as research on student learning in the domain (Wilson, 2005). When developing the levels within the construct maps, we concurrently developed ways to measure the theoretical constructs as well as how the items would be scored. Whereas the reading items are multiple-choice and included purposefully selected answer choices, the writing items are constructed response and require a rubric to score. The development of the answer choices and rubrics further clarified the levels within the construct maps. The validity of the items was again refined with the aid of cognitive interviews in which students explained their thought process as they constructed responses to selected items (Wilson, 2005). Specifically, we revised aspects that were confusing for students. Lastly, the results of pilots were used to refine the items and construct maps (Wilson, 2005). Masters’ (1982) partial credit model was used to analyze the results because it allows for different thresholds for different items, which happens when both constructed response and multiple-choice items are employed.

references

Masters, G. N. (1982). A Rasch model for partial credit scoring. Psychometrika, 47, 149-174.

Wilson, M. (2005). Constructing Measures: An Item Response Modeling Approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associate.

Wilson, M. (2005). Constructing Measures: An Item Response Modeling Approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associate.