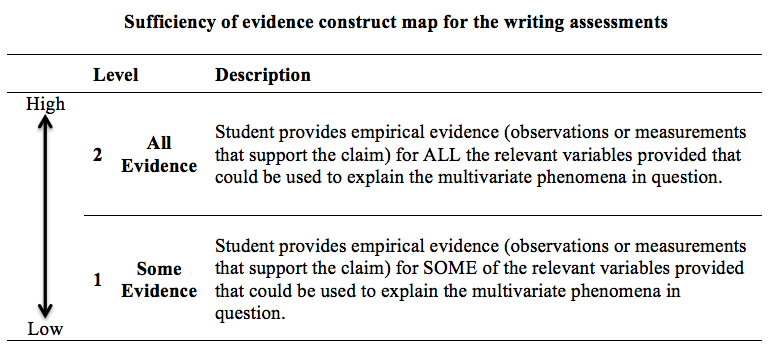

sufficiency of evidence

summaryAlthough students often try to use data as evidence (Sandoval & Millwood, 2005), we have observed that students tend not to use all the data available to them. This often happens when they are trying to explain a phenomenon that is impacted by more than one variable (e.g. depth and type of ground material both impact the intensity of an earthquake). We want students to use supporting evidence for all relevant variables, but we do not want them to include irrelevant data (e.g. wind speed does not impact the intensity of an earthquake). We wanted a way to capture whether students used all the relevant variables they had access to when writing an argument based on a multivariate phenomenon. Sufficiency of evidence, thus, captures how many of the relevant variables students used as supporting evidence (measurements or observations that support the claim).

|

definitions

|

Construct map

A construct is a characteristic of an argument. Construct maps use research on student learning as well as expert knowledge to separate the construct into distinct levels that characterize students' progression towards greater expertise (Wilson, 2005). The writing sufficiency of evidence construct map (see below) has two levels: 1) some variables and 2) all variables.

assessments

We developed four different writing items. While the topic of two of the items focuses on earthquakes, the other two items focus on volcanoes. The students’ response to a writing item is used to place their ability at one of the levels on the construct map. For instance, if a student only uses a personal story to justify their argument, then he would be placed at the “no variables” level of the sufficiency of evidence construct map. However, the sufficiency of evidence is only 1 of 5 different ways the students’ written response will be assessed. In addition to sufficiency of evidence, we encourage you to consider forms of justification, relevant-supporting evidence, multiple views, and reasoning (maps and rubrics are provided for each). While the students’ of highest ability will score high on all of the constructs, students of lower ability levels may have different strengths and weaknesses.

rubrics

Each of the four items are constructed response. Therefore, we developed a rubric to grade/score each of the constructed response items. Each rubric includes sample student responses for each level.

teaching strategies

It is our hope that, over time, students’ abilities will move towards the “all variables” level of the construct map. To assist teachers with this goal, we have developed teaching strategies. The following teaching strategies are intended to support students in moving to higher levels for Forms of Justification, Relevant Supporting Evidence and Sufficiency of Evidence, since we've found that it is difficult to focus exclusively on one area when teaching, and improvement in all of these areas can be seen when focusing on similar learning experiences that enhance the learning of all levels at once.

Construct Level

Level 2 & 3

(Mixture of Justification & More Important Justifications) Levels 0 & 1 (No justifications & Less Important Justifications) |

Description of Teaching Strategies

|

Resources

Lesson 1: American Eel Population

Lesson 2: Baking Soda and Vinegar

Lesson 1a: Fossil Tooth Lesson 1b: Fossil Tooth |

Tech reports

The tech report provides the psychometric analyses from pilot studies with middle school students.

references

Kuhn, L., & Reiser, B. (2005). Students constructing and defending evidence-based scientific explanations. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, Dallas, TX.

McNeill, K. L., & Krajcik, J. (2007). Middle school students’ use of appropriate and inappropriate evidence in writing scientific explanations. In M. Lovett & P. Shah (Eds.), Thinking with data: The proceedings of the 33rd Carnegie symposium on cognition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Sandoval, W. A., & Cam, A. (2011). Elementary children’s judgments of the epistemic status of sources of justification. Science Education, 95(3), 383-408.

McNeill, K. L., & Krajcik, J. (2007). Middle school students’ use of appropriate and inappropriate evidence in writing scientific explanations. In M. Lovett & P. Shah (Eds.), Thinking with data: The proceedings of the 33rd Carnegie symposium on cognition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Sandoval, W. A., & Cam, A. (2011). Elementary children’s judgments of the epistemic status of sources of justification. Science Education, 95(3), 383-408.